Can our tech calm down?

Amber Case is on a mission to make our products respect our time, attention, and humanity.

Last spring, I had a great conversation with Amber Case. Case is an author, a research director at Metagov, and a cyborg anthropologist (more on that later). She’s also the founder of The Calm Tech Institute, an organization that launched in May and aims to help companies design technology that “respects our time and humanity.”

Case specializes in the human relationship with technology and how we can create systems that work alongside us to improve our lives, not overburden them. We talked about that, and how she wants to bring back forgotten design tactics from the past. We also talked about cyborgs.

Case has fascinating thoughts on our relationship with new things, so I’m going to get out of the way and let her share some of those ideas. Here are excerpts from our talk, with a little light editing for clarity.

First things first: Cyborgs.

“Cyborg is another one of those terms that seems like RoboCop or Terminator, but actually came from a 1960 paper on spacecraft. The definition is any organism to which exogenous components are added for the purpose of adapting to ambient spaces. Which just means anyone in a spacesuit has added some stuff so that they can survive. And when I say we’re cyborgs, we’ve been cyborgs since the first tool. We add something to ourselves in order to extend—extend our teeth with a knife, extend our fist with a hammer.

We’ve made these external tools that are extensions of our mental selves and now we have this ridiculous exocortex that makes us super high tech cyborgs that we’re kind of clicking into all the time.”

What it means to be a cyborg anthropologist.

“A traditional anthropologist might go to another country and say, how fascinating these people are. A cyborg anthropologist goes to their bedside phone and says, what a weird person I am. It’s only been 15 years, but now I wake up next to this thing. It cries and I have to pick it up and soothe it back to sleep. I might take care of feeding it better than I feed myself. And I substitute its needs for my own. It’s a very cyborg behavior.

It’s important to investigate how many tools, how many pieces of technology, how many systems we touch in a given day. Technology, like a gas, seems to have expanded to fill up all of our available space and time. So much so that we don’t even have time to think about what we’re doing with it.

Cyborg anthropology is such a weird phrase, but it gets people to stop and reconsider how they use things or who they are.”

Why it’s important to interrogate our relationship with tech.

“I think the future is outdated. I think our version of the future is from the ‘50s and ‘60s, and we keep trying to make something that we saw in movies and we saw in science magazines, without questioning what the present actually needs. And I think having better tools to investigate the past is going to help this slow shift from things that take our attention and our cognitive drain, to stuff that works alongside us, and allows us to steer what it does. But fundamentally, we’re the ones in control.”

Product designs from the past that worked for us, not against us.

“In a car, you get a light when something goes wrong, not when it’s right. You’re actually informed by the rearview mirrors and your foot pedal. You’re not even having to use your eyes to speed up. The interfaces in the car are using multiple senses. And oddly, you feel more at peace if you really get into driving, because you’re informed without being overburdened.

I think there’s this huge difference between how technology is designed today, and how it was designed in the past. From a SKIL saw, or a lighter, or a car. These are complex systems and objects, yet they aren’t actually overburdening. You can take a drive to relax, put some of that information in part of your cognition, and think about something else.”

And how that compares to some of the products we use today.

“You can have a conversation while you drive. You can’t really have a conversation while you’re scrolling through Reddit. It’s really hard.

When you go home, you don’t want to have to be the systems administrator of your home. You don’t want to have to talk to your washer and dryer. But there’s this big assumption that the future is about communicating with your electronics and everything has this goal. And honestly, most of it have become terrible roommates. It’s like we have like 10 to 20 new roommates in our lives. And they’re constantly bothering us. And they even prevent us from going to sleep because they demand our attention.”

“It’s like we have like 10 to 20 new roommates in our lives. And they’re constantly bothering us. And they even prevent us from going to sleep because they demand our attention.”

An app that helps.

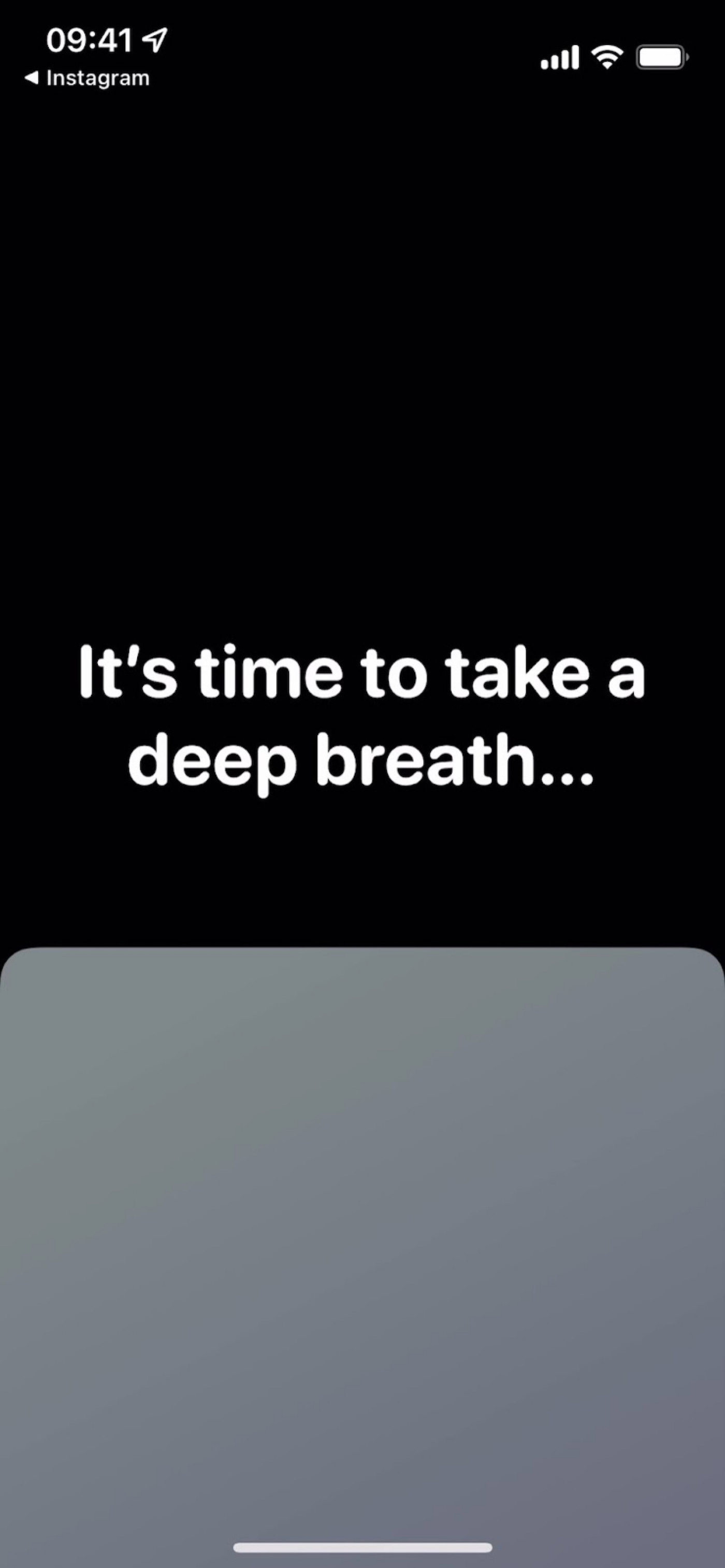

“The one thing that’s helped me—because Instagram was really my kryptonite—was this app called one sec, where it just tells you to take a deep breath and obscures the screen and you have to wait for 10 seconds while the screen occludes. Then you have to say, “yes, I really want to open Instagram.” That took my clicks of opening Instagram from 1,000 times a week to once a week. And it’s saved me like a cumulative couple weeks of my life already.”

Interesting things

Amazon Decides Speed Isn’t Everything, by Louise Matsakis, The Atlantic 📄

High Above New York, a Battle for Tourist Dollars, by Todd Heisler

and Mekado Murphy, The New York Times 📄 (free-to-read gift share 🎁)

The Unbranding of Abercrombie, by Chantal Fernandez, The Cut 📄

Thanks for reading. See you next Sunday.

Eric