The IKEA effect and AI chatbots

We value things more when we make them ourselves. How will automation change that?

You know those artificial intelligence chatbots that have started popping up in email, social media posts, and documents? The ones that can help you write something or generate an image for you? Whenever I see them, I can’t help but think about something called the IKEA effect.

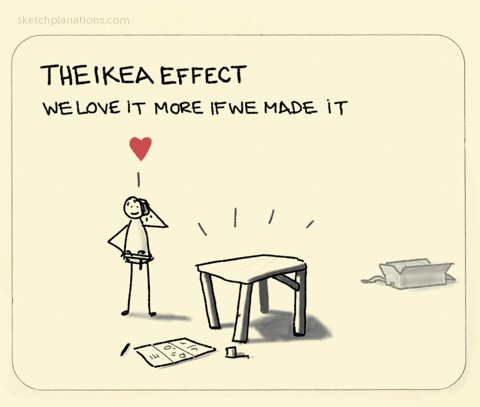

The IKEA effect is a psychological concept coined in a 2012 study in the Journal of Consumer Psychology. It says that we value something more when we create it ourselves.

In an experiment, one group of participants constructed an IKEA storage box (this group was called “the builders”). A second group was given an already-assembled storage box to inspect (they were the “non-builders”). Both groups were then asked to decide how much they’d be willing to spend on the item. The builders group bid significantly more for their boxes. It was the same product, but they valued it more because they put it together themselves.

Researchers tested the theory in additional experiments, using origami and Legos to see what would happen with different types of creations. Again and again, they saw the IKEA effect in action—value was higher for self-assembled stuff.

Amateur origami makers even viewed their frogs and cranes as similar in value to origami projects folded by experts.

…while the non-builders saw the amateurish creations as nearly worthless crumpled paper, our builders imbued their origami with value. Indeed, builders valued their origami so highly they were willing to pay nearly as much for their own creations as the additional set of non-builders were willing to pay for the well- crafted origami made by our experts.

Here are a few other interesting conclusions:

We value things we create ourselves more than those created by others.

Completion matters. If we don’t finish something, or we destroy it, the valuation plummets.

This may be why coworkers sometimes fixate on their own ideas—they perceive them as more valuable (even if they’re not).

It may also be a factor in why someone will stick with a project even when it’s failing (the sunk cost fallacy).

The IKEA effect works across utilitarian projects (building furniture) and hedonic creations (folding origami).

How AI-generated creations alter what we value

Back to the point I started with—those AI helpers that seem to be popping up everywhere, nudging us to let them create for us. There’s no playbook for deciding whether or not we should let new technology take the wheel and create stuff for us. Yet the prodding will continue and, I think we can all agree, increase as AI innovation intensifies.

I think the IKEA effect can help guide these choices.

On the one hand, are there things you currently do that you overvalue, thanks to the IKEA effect? Are you in love with a cumbersome spreadsheet that eats up hours of work each week because you put so much time and effort into it? Kind of like that MALM six-drawer dresser you spent that Saturday afternoon laboring over? Maybe those inherently problematic parts of work and life (the ones that you’re being tricked into thinking are better than they actually are) are more worthy for automation.

On the other hand, perhaps there are things you create that you really do value. Because they bring you value in the form of joy and a feeling of accomplishment. Maybe the process of struggling through a creative act is good for your brain.

Or maybe, in some cases, as the researchers found, you want to create something yourself so you can show it off to your friends: “many of our participants who built Legos and origami … mentioned a desire to show them to their friends, suggesting that the increase in willingness-to-pay for hedonic products may arise in part due to the social utility offered by assembling these products,” the authors wrote in the paper.

There’s no clear answer for how to navigate this new reality. But as we do, it’s wise to start by understanding our own perception of value in the things we make. Do you value something you’re creating? If so, why? No one can determine what you derive value from except for you. Asking those questions seems like a useful starting point.

Thanks for reading.

Eric